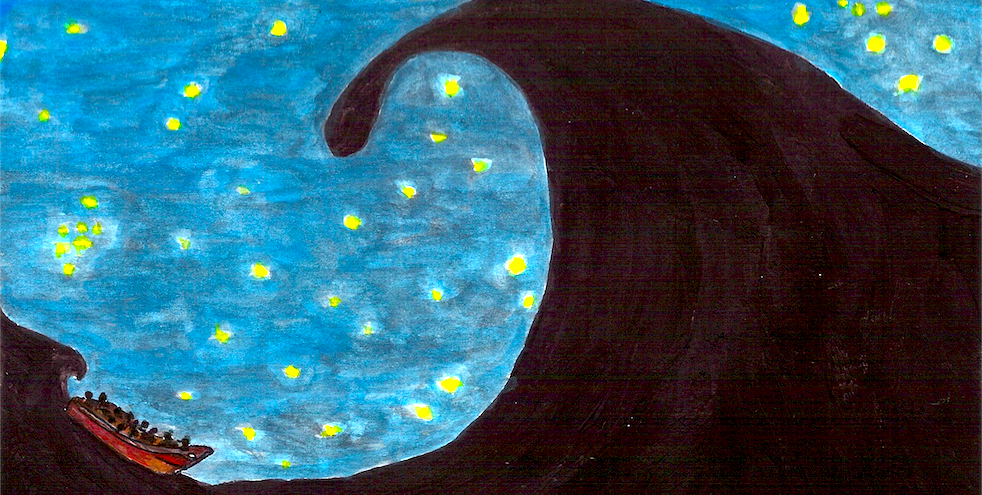

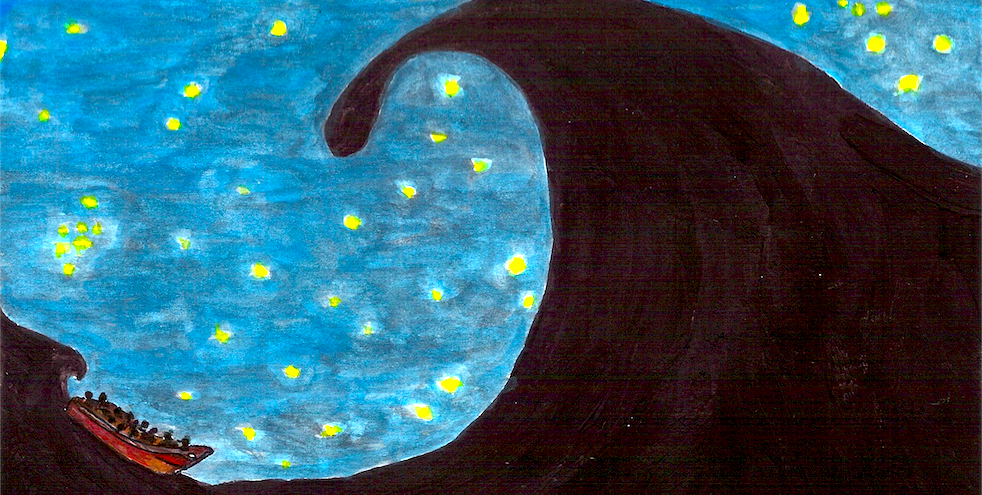

The entire adventure itself was like a big wave in the sea.

It mounted, surged fiercely and eventually rolled back into the large homogenous mass it came from, and life continued.

At least that’s how it was conveyed to me.

Chung, Ly, Chinh and Thu found a place to live, learned a new language, went to school or got jobs, formed relationships, a few got married and had kids.

I’m one of those kids.

In fact, I was the first kid born to this group of people in Australia and Ly is my mum.

Growing up, this story was told to me in all sorts of ways; as bedtime stories, to win arguments ("Of course you'll be fine when you move out of home. It's not like when I moved out of home!"), to tease ("You made the rice too crunchy, it reminds me of being in jail!").

Now I've asked for the official recount. Looking back on these interviews, however, I realise there's still a glint of bedtime story in there.

Note:

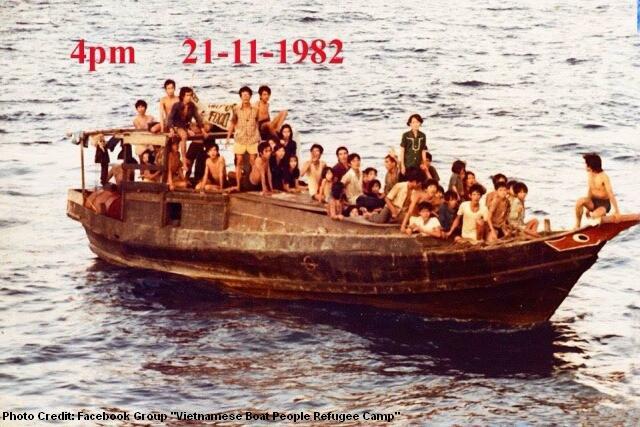

Obviously when you’re running for your life, no one stops to take photos, or take note of the exact date, or how long it took to get from the island to the international border.

Where these numbers, dates, facts and statements were corroborated across interviewees, or if they were verifiable through conventional fact-checking methods, I kept them in the story.

Where there are few facts to check due to little record, it’s important to begin a collection.

Where memory is imperfect, testament still holds weight.

Hopefully this adds something to the archives.

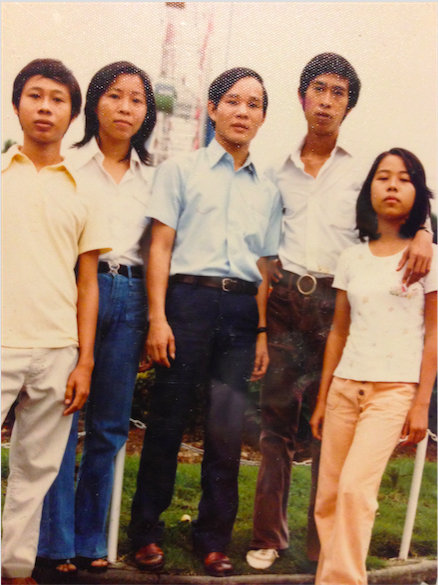

At the time, the family were living in Nha Trang, a small fishing village at the centre of the east coast of Vietnam, but not everyone was at home.

After the Fall of Saigon in 1975 my grandfather or Ong Ngoai, a Colonel in the South Vietnamese airforce, was arrested and imprisoned in a re-education camp.

The family were blacklisted as traitors and their every move was monitored.

My grandmother, or Ba Ngoai, was left to care for her six kids.

Chung was 25 years old and had been working as a forest ranger in the jungle. Since it was known he came from a family of traitors, Chung found himself stuck in a dead-end job. Promotions were out of the question, as were other kinds of substantial employment.

Ly was 22 and about to begin her third year at university in Saigon. However, her first failed attempt at escaping the country and stint in jail saw her miss the beginning of semester. Knowing her classmates and teachers would suspect what she was up to, she came back home to Nha Trang instead.

Thu, 18, had just finished high school but couldn’t enrol at university because her name was blacklisted.

Chinh, 16, was still in high school.

Their youngest brother, Anh, had been sent to live with his Aunt in Saigon who could afford to take care of him.

Their oldest brother, Hieu, was serving a one year sentence in a prison camp for attempting to escape Vietnam via foot through Laos.

The main thing to know about planning an escape is that it takes money and the ability to organise everything in secret.

The Vietnam War had divided the country into two sides: victors and traitors. After communist victory, those who fought for South Vietnam were driven underground for fear of persecution. On the surface it was hard to know who truly had allegiance to whom.

“We didn’t trust anyone,” Thu said.

“Not even friends. We could trust the family, but not anyone else, even best friends. You never knew if they would turn on you or report you.”

In this political climate, finding people who wanted to escape and who could be trusted was fraught.

“There are a thousand ways to cheat you,” Chung told me.

“One guy could say, ‘I have a boat,’ and once you pay him he could disappear forever. Next thing you know the government is at your door and they put you in jail.”

Those who were found to be the main architects of such schemes were executed by the Viet Cong and held up as an example to others.

Ba Ngoai took it upon herself to find trusted people with whom her children could escape.

She sold their house in Saigon to pay for supplies and a boat.

Chung and two of his friends were tasked with taking care of supplies.

He told me for an escape, you need four things: water, petrol, a boat and a compass.

The plan was to hide out on a nearby island where nobody lived.

Chung and his friends would slowly build up supplies and hide them in a cave on the island.

Over a period of ten days, those escaping would sneak onto the island and hide out until everyone arrived.

They would come in small groups to avoid looking suspicious.

His friend who organised the boat would eventually turn up with it. Everyone would then transport the supplies from the island onto the boat, and off they would go.

At the time, owning a compass was illegal due to the mass exodus of people escaping by boat. They were in high demand and as precious as gold. Chung managed to obtain one off the black market.

As for water and petrol, having a little bit was normal, but owning a lot looked highly conspicuous.

In the video below, Chung details how he got around it.

“Now that I have told that story, I remember how difficult it was back then," Ba said to me after recounting it all.

"Ong was in prison. It was me and your mum and aunty and uncles at home that I had to look after. There wasn’t any other period in my life as hard as this period.”

By this time, Chung and Chinh had been hiding out and building up supplies for around two weeks.

"It was very scary because we couldn't allow ourselves to be seen," Chinh said.

"The island was made up of large rocks and bush. We would spend most of the time hiding behind them or lying down."

They had arranged for a local fisherman to bring them food each day. When he arrived they would hop onto the boat without being seen, eat, and sneak back onto the island.

Out of Ba's six children, four were about to attempt escape.

Her oldest son Hieu was in prison.

Her youngest son, Anh, she chose to keep behind.

Thu and Ly were the last to make their way to the island. The escape plans were coming into full swing.

It was around 1am when the boat arrived to take them away.

I always admired my family’s ‘she’ll be right’ attitude - I have a theory that the original white Aussie larrikin was actually Vietnamese - but getting on a boat with no map, no food and no back up? That’s wild.

It was late July, 1980. The height of monsoon season.

The timing of this was intentional. During monsoon season, fewer people attempted to escape which meant fewer patrols, minimising the risk of being caught.

However, this also meant faring rougher seas.

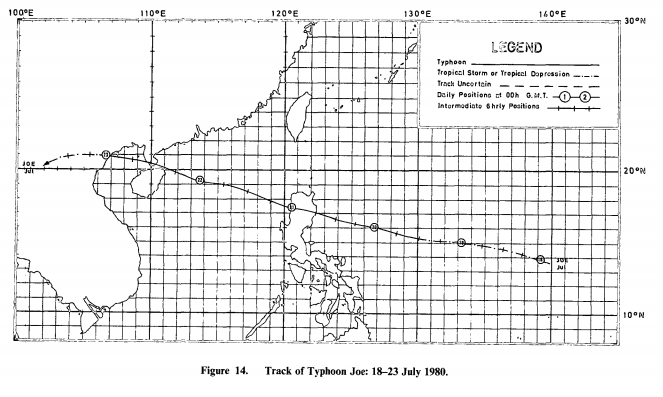

Typhoon Joe began as a tropical depression near the Caroline Islands on July 16 and grew to be a tropical storm two days later.

A day after that Joe became a full blown Typhoon, making it’s way from the Philippines across the South China Sea towards Vietnam.

Though I don’t have the exact dates for when Chung, Chinh, Ly and Thu made their journey across the sea, the general direction they were going in, combined with Typhoon Joe’s late July rendezvous line up.

They would not have been close to the eye of the storm (it's more likely they were further south), but it would have been close enough to have inspired the rough seas they described.

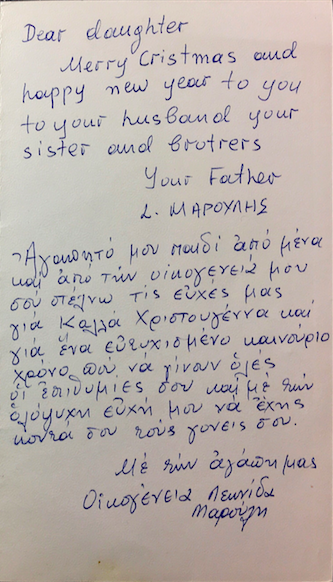

His name was Leornard Maroulis and he kept in contact with Ly via letters right up until he died.

Every year for Christmas she sent him a present. They were usually Australia themed: a calendar, a painting of native flowers and other pretty ornaments.

Ly was working as a cook at the Epworth hospital when one of her co-workers announced she was going back to Athens to visit her family. Mum asked her to make a special delivery to Mr Maroulis: an invitation to her upcoming wedding.

Her co-worker came home with a present from the Captain: two dolls in traditional Greek costume, a good luck charm for a long and happy marriage. They are displayed in her home to this day.

Captain Maroulis’ ship was delivering containers of cars to South Korea.

They made a stop over in Japan, and Chung, Ly, Thu and Chinh were granted asylum at a refugee camp in Fukuoka.

Ba recieved a telegram 20 days after their departure that told her they were safe.

The siblings stayed in Japan for just over a year before receiving VISAs to live in Australia at the end of 1981.

(While eating a sweet potato)

Just don't ask me why Ong has a drill.